2026-02-06: A laser is just another bicycle tire: Instrumental work in the hangar

What do a laser and a bicycle tire have in common? It’s an automobile valve, of course!

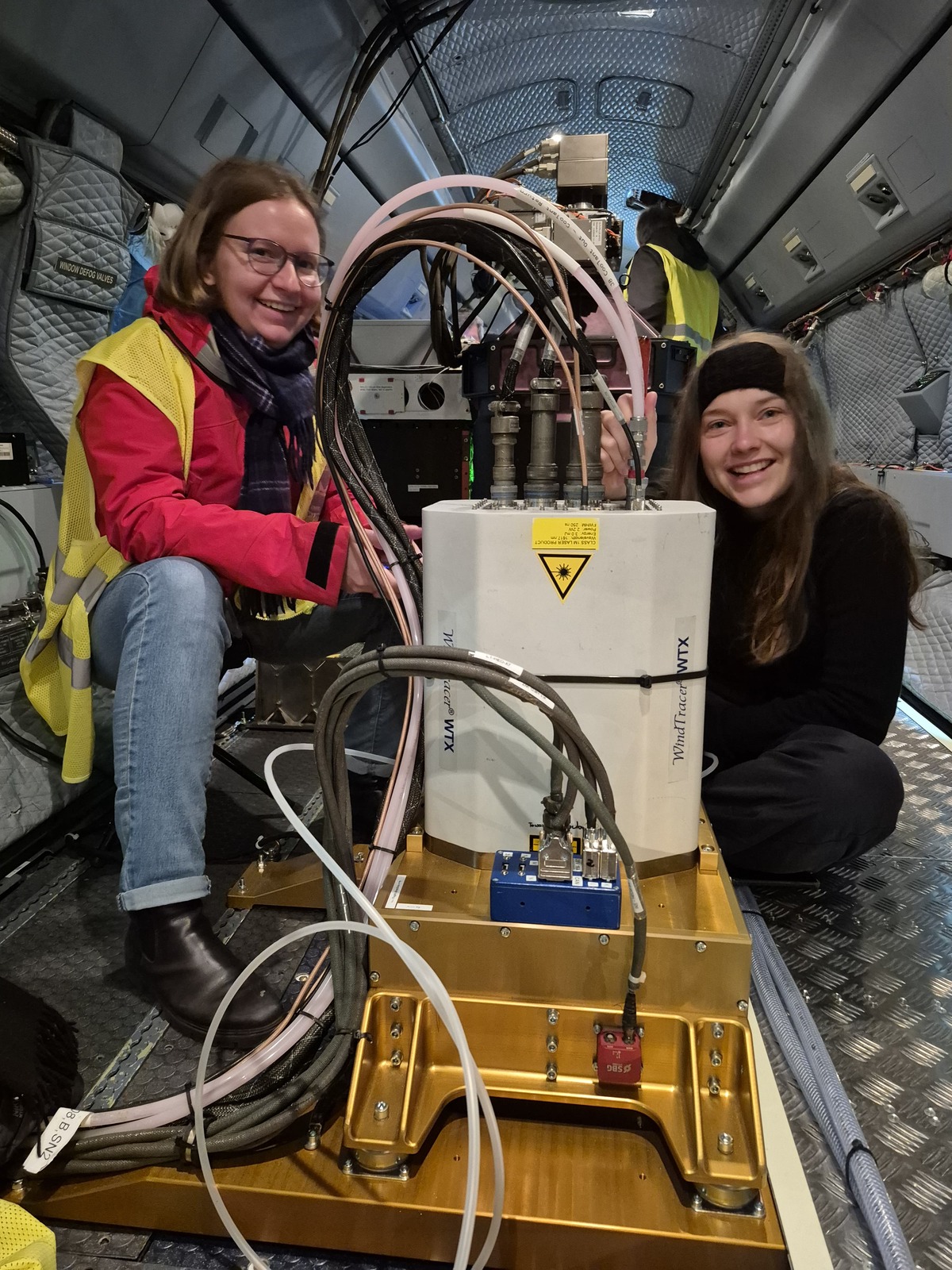

The laser of our wind lidar HEDWIG indeed sports an automobile valve next to cables and hoses containing cooling liquid. The laser performs best when the relative humidity in its casing is low, which we have to ensure by flushing it with air – a task not much different from pumping a bicycle tire after having repaired it.

Therefore, in the early morning before the research flight RF09 Midleton, my colleague Katharina and I went to the hangar to flush the laser with air. The air is contained in liquid form in a gas cylinder, which is connected to the lasers’ automobile valve with a hose. A pressure valve on the cylinder regulates the outflow. We flushed the laser for one minute, then let out excess air by pressing the valve, as one would with a tire. Then we flushed again to replace the old, humid air in the casing with fresh, dry air, repeating the cycle over and over. With success: The relative humidity was 13% when the laser was started, a new record low!

The instruments are the backbone of a measurement campaign. That’s why, the work on the instruments in the hangar is of great importance. Every morning before a flight, scientists and instrument managers wake up early to prepare their instruments, ensuring they run smoothly for 8 hours straight. While the flushing with air is important for the HEDWIG laser, it is of course not the only work my colleagues and I have to do in the hangar. Since we are close to the city of Limerick, I have summarized my thoughts on the instrumental work in a poem of the same name:

For an airborne HALO campaign

Some necessities clearly remain

The work in the hangar

Is of elaborate manner

To ensure HEDWIG works on the plane

Elina Köster (DLR)

2026-02-05: The Lidar Limerick

There once flew two lidars on HALO

For winds and wet air - quite the combo

We plan the best flight

Chase fluxes with might

Strong winds set out pulses aglow

Clouds? Nope. But aerosols YES!

Relative humidity makes our retrievals the best

We skim the oceans low

Grill fish with a glow

Go veggie to balance the mess.

-Unknown poet

2026-01-27: Chasing winter storms over the Atlantic

This is a shortened English adaptation of a blog which originally appeared as MeteoSchweiz Wetterblog on 26 January 2026 (https://www.meteoschweiz.admin.ch/ueber-uns/meteoschweiz-blog/de/2026/01/auf-der-jagd-nach-winterstuermen-ueber-dem-atlantik.html).

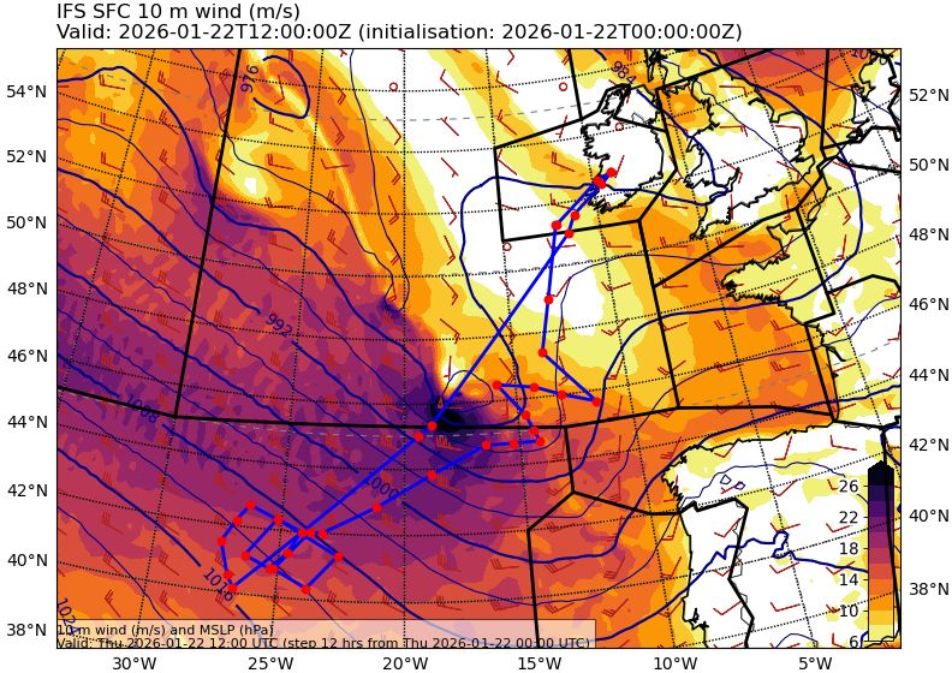

Last Thursday, winter storm "Ingrid" developed from a weak disturbance along a cold front into a powerful low-pressure system within just 24 hours. With a core pressure of around 960 hPa, it reached Brittany on Friday morning. A NAWDIC mission first investigated the absorption of moisture from the ocean into the atmosphere near the Azores. On its return flight to Ireland, HALO then crossed the core of the low. Planning such measurement flights is very challenging due to the dense air traffic over the North Atlantic and the uncertainties in forecasting. Nevertheless, measurements were successfully carried out both in the core of the low and above the developing strong wind field.

Winter storm Ingrid marked the beginning of a weather situation in which low-pressure systems are once again reaching Switzerland. Last week, Switzerland was still on the edge of a blocking high centered over Scandinavia and Northern Europe. The low-pressure systems moved further south and mainly affected the Iberian Peninsula and the Mediterranean region. However, the high is now moving towards Greenland, clearing the way for low-pressure systems.

Nevertheless, the low-pressure systems continue to track relatively far south because the high over Greenland and the polar region is blocking the typical path to Northern Europe. As a result, there will again be particularly high precipitation in the Mediterranean region this week. Conversely, one of the climatologically wettest regions in Europe – the west coast of Norway – remains surprisingly dry.

The ECMWF's subseasonal forecast also indicates that blocking highs over the Greenland region could continue to influence the large-scale weather situation in Europe in the coming weeks. This means that NAWDIC will continue to target low-pressure systems that tend to move along southern tracks.

2026-01-26: My first flight on HALO

On Thursday was my first flight on HALO, and it still feels a bit unreal. I first heard about HALO in a lecture during my meteorology studies. Back then, these measurement campaigns sounded exciting, but not something I expected to take part in myself.

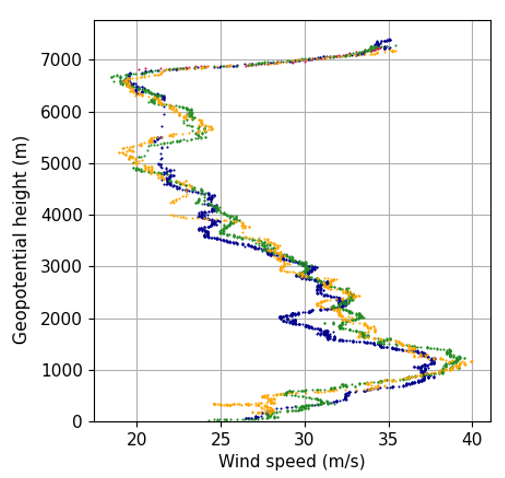

Part of what made it unreal was how spontaneous it was: I was told that I would be flying only the afternoon before the flight day. So, I learned how to use the dropsondes, and early the next morning we headed to the airport. On board HALO, we prepared the dropsondes, and shortly after, we took off from Shannon towards the Azores. During the flight, I was responsible for releasing the dropsondes. The sondes measure vertical profiles of temperature, humidity, and wind.

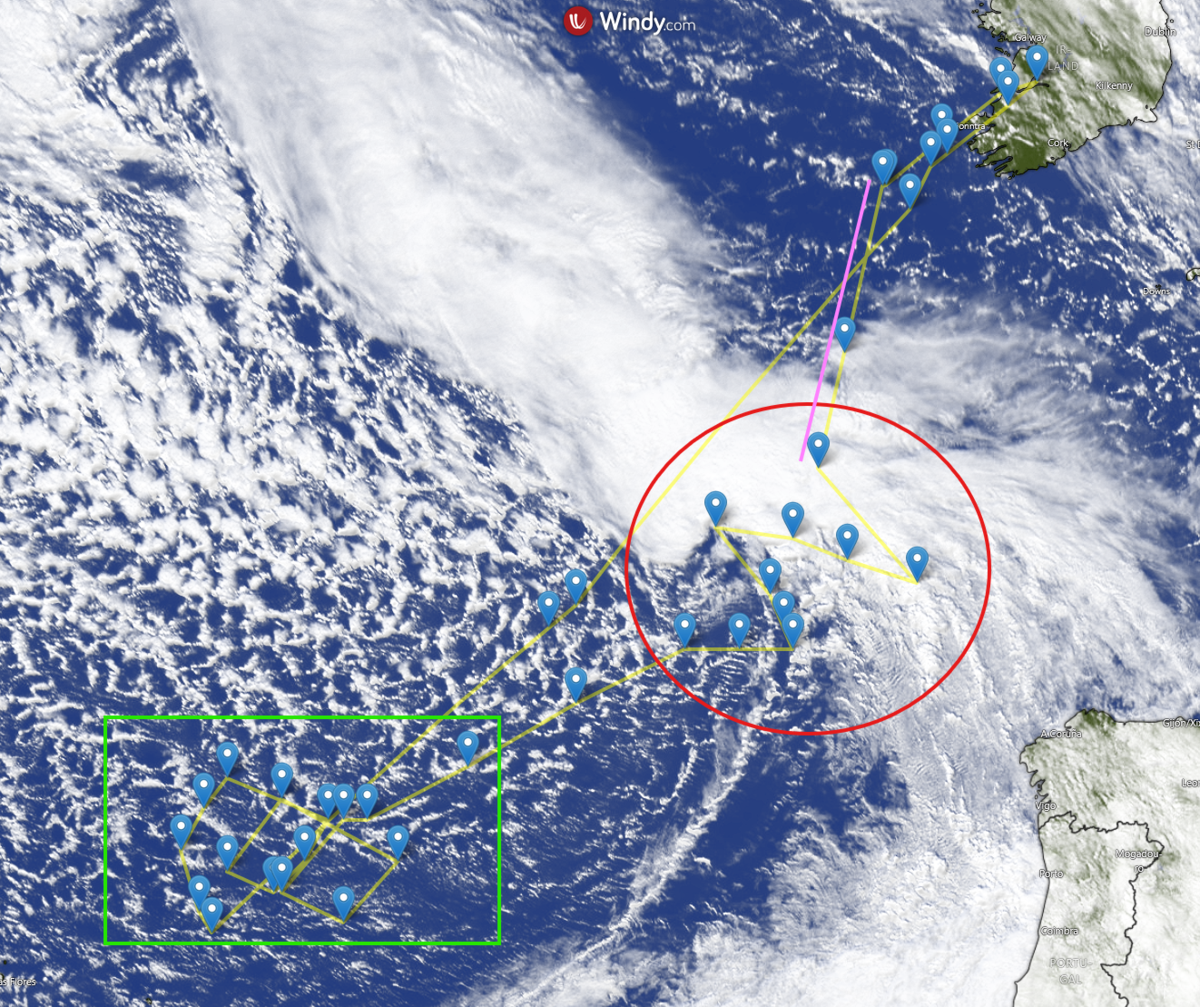

Not only was this flight exciting because it was my first one, but also from a scientific perspective: We first headed towards the Azores to measure increased latent heat fluxes within the cold sector of a low-pressure system (green box). The fluxes were measured with wind and water vapor lidar. After flying a formation whose shape looked a bit like an eight to measure the fluxes, we turned north towards a rapidly intensifying low-pressure system moving eastward (red circle). Hitting its location so precisely was a highlight of the flight, especially given the large forecast uncertainty during planning the flight. Thanks to the flight planning team and great ground support, we were able to catch it.

Flying through a cyclone is not only scientifically fascinating but also something you definitely remember on board, thanks to the turbulence :) Even though it was very shaky, we were able to drop the sondes as planned, and the first quick looks already looked great. On our way back to Shannon, we were also able to underfly EarthCARE (pink line), which intersected the same low-pressure system. All in all, a successful first flight with HALO.

Annabell Weber (DLR)

2026-01-23: NAWDIC-AR Coordination with the Global Atmospheric River Reconnaissance Program

The North Atlantic Waveguide, Dry Intrusion, and Downstream Impact Campaign (NAWDIC) is an international field campaign designed to improve the understanding and prediction of high-impact weather over Europe by observing upstream dynamical and thermodynamical processes across the North Atlantic. Within this framework, NAWDIC-Atmospheric River (NAWDIC-AR), a subset project of NAWDIC-HALO missions, led by Alexandre Ramos (Karlsruhe Institute of Technology), focuses specifically on improving predictability of significant impacts over Europe by sampling AR moisture source regions as they propagate across the North Atlantic toward Europe.

NAWDIC-AR is occurring alongside several coordinated field campaigns simultaneously underway across the Northern Hemisphere, all aimed at advancing the prediction of high-impact weather systems. Among these is Atmospheric River Reconnaissance (AR Recon), a long-running, annual field program led by co-PIs Marty Ralph (Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes/UC San Diego/Scripps Institution of Oceanography) and Vijay Tallapragada (NOAA/NCEP/EMC), focused on targeted observations of ARs that pose significant hazards to the United States. Current operations involve multiple Air Force C-130 and NOAA G-IV aircraft based in California, Hawaii, and the southeastern U.S. to sample ARs upstream of the U.S. West Coast and Atlantic ARs threatening the U.S. East Coast to observe moisture transport, winds, and thermodynamic structure.

In addition, a NASA-funded North American Upstream Feature-Resolving and Tropopause Uncertainty Reconnaissance Experiment (NURTURE), led by PI Steven Cavallo (University of Oklahoma), will begin operations on 26 January from Goose Bay, Canada. NURTURE aims to quantify how perturbations poleward of the jet stream—particularly in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere—modulate jet variability and the predictability of high-impact weather.

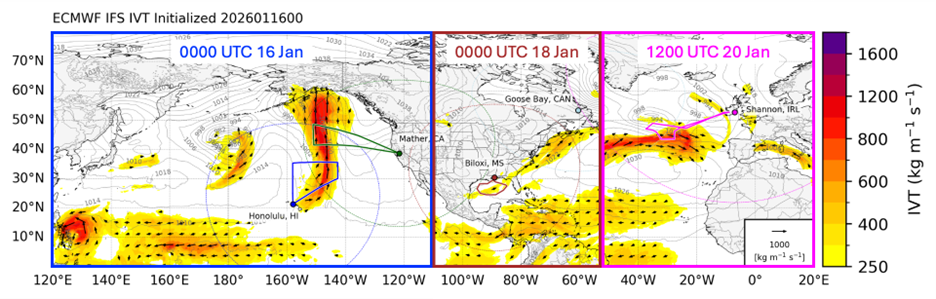

Building on these basin-scale and cross-basin efforts, the concept of a Global Atmospheric River Reconnaissance Program (GAARP) was developed by PIs Marty Ralph (CW3E/UCSD/SIO) and Vijay Tallapragada (NOAA/NCEP/EMC). GAARP envisions coordinated global AR observations across multiple ocean basins, leveraging aircraft, radiosondes, and international partnerships to follow ARs throughout their life cycle. Viewed in a Lagrangian framework, as illustrated by the time-evolving IVT structures in the accompanying map, these efforts aim to advance week 2 forecasts by sampling all ARs in the Northern Hemisphere, representing a major step toward a globally coordinated AR observing strategy.

Peyton Capute (CW3E)

2026-01-16: (HALO)²

I often talk to people who assume that campaign life is much like being on vacation—especially when destinations include the Caribbean or New Zealand. And indeed, many vacations start by waking up at 05:30 to head to the airport and catch a flight. Today, the flight we had to catch was HALO’s first research mission from Shannon. However, instead of queueing at security, grabbing a coffee afterwards, and waiting at the gate, a research flight requires thorough preparation.

Depending on the instrument, this can mean arriving at the hangar up to four hours before take-off to heat up, calibrate, flush, or clean systems. Once HALO is towed out of the hangar and the flight crew—including instrument operators, pilots, and technicians—arrives, the aircraft quickly becomes crowded: the familiar hustle and bustle of a flight day. Instrument-responsibilities are handed over from the preparation to the operation teams, final reports are exchanged, and everyone not scheduled to fly leaves the aircraft. And just like that, HALO is off on a seven-hour mission.

For the scientists remaining on the ground, the day continues with weather briefings, flight planning, and data processing, while staying in constant contact with their colleagues on board to provide support if needed.

Today’s scientific targets included measuring enhanced surface latent heat fluxes in the cold sector of a cyclone and capturing another transition from tropospheric to stratospheric air masses. The former is achieved by combining water vapour measurements from a differential absorption lidar with vertical air motion derived from a wind lidar. The latter is best observed using in-situ measurements of ozone and nitrous oxide. These two trace gases are anti-correlated: when crossing from the troposphere into the stratosphere, one ideally observes an increase in ozone accompanied by a simultaneous decrease in nitrous oxide. Neither of these processes is visible to the naked eye. However, one of the operators provided this photo: a halo observed from HALO—one could even say (HALO)².

Anja Stallmach (LMU Munich)

2026-01-14: HALO touchdown in Shannon

While my colleagues from the specMACS team had to travel to Ireland commercially yesterday, I opted for the business jet—complete with all the perks of private aviation: a direct connection from Oberpfaffenhofen to Shannon, complementary coffee and only 5 other passengers sharing the aircraft with me.

Even though HALO is a Gulfstream 550 jet, you won’t find carpeted floors or champagne flutes being passed around. The luxury we experience on HALO is of a different kind. HALO brings atmospheric scientists together, enables us to explore synergies between different instruments and carries us close to the phenomena we otherwise only analyze on computer screens in our offices.

Today therefore marks the start to the HALO measurement phase of the NAWDIC campaign. Although we had a direct connection to Shannon, HALO took a small detour via Switzerland and France, before doing a final loop over the Atlantic to sample a pronounced tropopause fold and boundary-layer cumulus clouds in the cold sector of a preceding cyclone. Ireland greeted us with sunshine and the hangar was crowded with our large welcome comittee.

HALO has touched-down in Ireland—here is to a successful, storm-laden and joyful campaign!

Anja Stallmach (LMU Munich)

2026-01-13: Preparing for the Storm: Maintenance and Measurement in Brittany before the IOP

Loren:

I arrived at the 2 December in Brittany. Arriving at a measurement campaign for the first few weeks of operation, means that there are still some additional set ups to do. So, I spend my first week with driving and carrying around the house and the laser of a DIAL in addition to the first station maintenances in quite strong winds and rain. However, it was a fun experience and caused amazing cloud formations.

Viktoria:

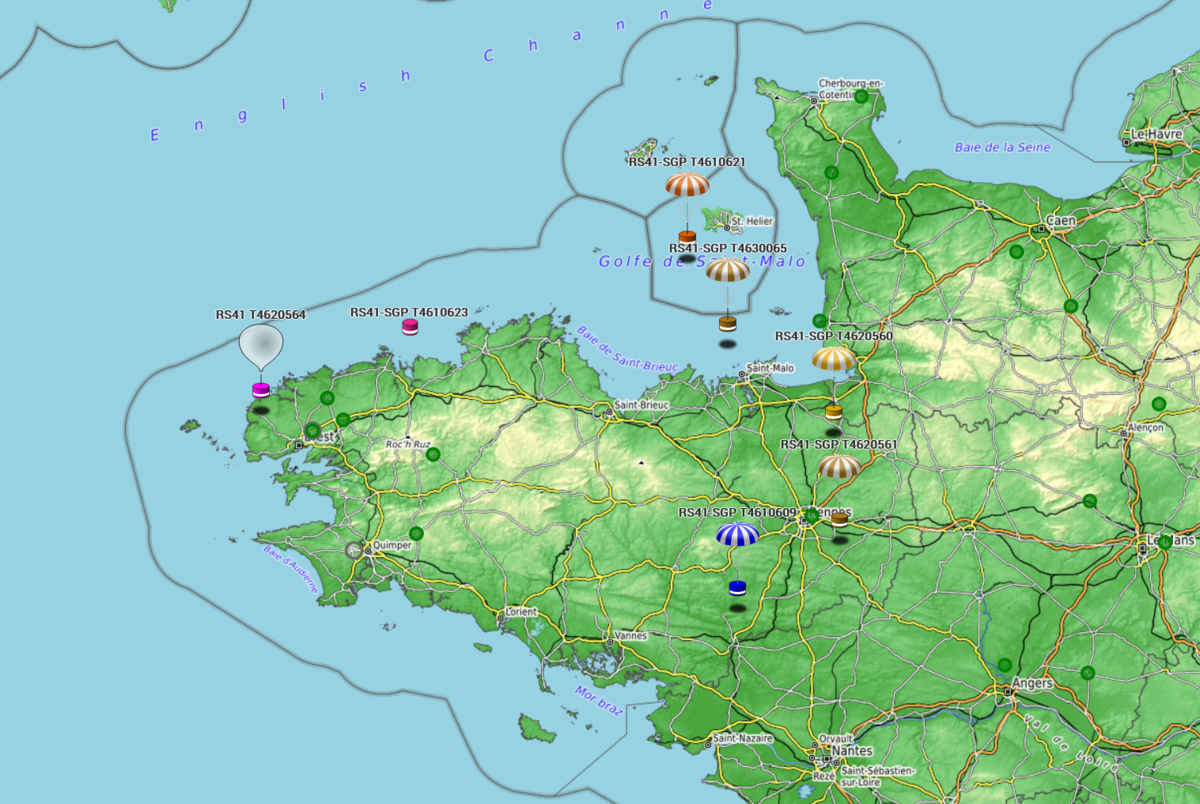

When I arrived one week later, it was in the midst of an IOP and I was first greeted by heavy precipitation when stepping out of the train station. An atmospheric river arrived at the French coast line the night before. This motivated an IOP from 08 to 09 December with 3-hourly radiosondes launches at the main station in Porspoder to get a detailed overview of the atmospheric conditions during this event and the associated heavy precipitation and strong winds.

After the storm had subsided, we were accompanied by rather calm and sunny conditions for the next few days. With temperatures around 10°C, it often felt more like early autumn here, although it was in the middle of December. While these were not the weather conditions we are interested in, it was a great opportunity to do some maintenance at the main station and the four meso stations. Maintenance includes checking the alignment of measuring masts, carefully cleaning lenses and measuring devices in case of contamination, replacing the desiccant in the Doppler wind lidars, and much more. Since we launched multiple radiosondes during the IOP, we also decided to fill up the auto launcher to be prepared for the next events.

Especially at the main site which is located close to the coast there were a lot of striking weather phenomena to observe. Rainbows occurred on several days and on one day in the evening while tending to the energy balance station, we managed to capture the formation of marine boundary cumulus in the sunset. We’re looking forward to the detailed measurements from the campaign and new insights of the interaction of the ocean and coastline.

Loren Schäffler and Viktoria Dürlich (KIT)

2026-01-12: A Golden Case for NAWDIC in Brittany?

When I prepared for my first field trip a few days after new year’s, I could not have known how intense and exciting my stay in Brittany would turn out!

In the second week of January, winter storm Elli (named Goretti by Météo-France and Elli in Germany) developed over the North Atlantic as a frontal wave and intensified under strong upper-level forcing. The models predicted strong wind gusts in the warm sector, accompanied by a pronounced cloud head (bent-back front) with a likely formation of a sting jet that would pass directly over the NAWDIC KITcube site in Brittany in western France.

Based on this prediction, the NAWDIC scientific lead issued an intensive observation period (IOP) with a high frequency of radiosonde launches during Elli’s passage. For me – having neither been involved in field measurements nor any radiosonde ballon launches before – there could not be a more exciting case for my first campaign experience! And not only that: Elli developed to a textbook-like example of a midlatitude cyclone! No theoretical lecture could have thought me the dynamics better than being on site, frequently checking weather maps and KITcube’s remote sensing data, launching ballons and tracking their flight paths!

Over the course of the 8th January, we launched 11 radiosondes. The 18:30 UTC ballon experienced such high windspeeds that it got pushed halfway out of KITcube’s autolauncher vessel. With adrenalin up high, we launched another sonde right after. This time, due to turbulence, it hit the vessel multiple times before it finally departed upwards. Watching the strength of the storm throughout the “eyes” of the autolauncher cameras was a unique and unforgettable experience. Eventually, Elli’s core passed north of Brittany with windspeeds of up to 154 km/h measured on the Channel Islands in the night of 8th January.

Two days later, Elli’s leading warm front collided with cold polar air over parts of Western Europe, creating wide bands of snow across the northern and eastern parts of Germany. Meanwhile, we monitored the impacts Elli left in Brittany. Multiple power outages affected the KITcube sites any some of the devices had to be rebooted manually. Now, one week after our arrival in Brittany and four days after the storm, Brittany shows again its sunny side. But stay tuned, the next intensive observation period is just about to come!

Julia Thomas (KIT)

2026-01-10: When the wind is in the west, then it is the very best

When I came to KIT more than two years ago, the year 2026 seemed to be very far away. Preparing a major aircraft campaign like NAWDIC requires several years for good reasons. You need to think about how to organize a typical campaign day, to share the weather forecast and flight planning duties among more than 50 participants, and to consider instrument limitations and ATC restrictions, not mentioning the scientific coordination between all sub- and partner projects, transport logistics, travel planning, finances, and outreach activities. The complexity of all this can be overwhelming and fascinating at the same time, but also very abstract in the end.

Luckily, time flies and as soon as 2026 has finally arrived, suddenly everything becomes very real. Also the weather seems to remind us that it's time now. While storm Goretti rushes through the English Channel and hits Northern France with winds of more than 200 km/h (not far away from the KITcube location), we travel to Ireland to start into our six-week NAWDIC adventure. Since HALO will only arrive next week, we have enough time to move into our flat, to unpack the instrument equipment from the shipping containers and to set up the meeting rooms. Everything is ready now. We cannot wait for more storms to come and finally for NAWDIC to begin!

Bastian Kirsch (KIT)

2025-12-17: Scientific Test Flight of HALO

Entering the hangar with the HALO research aircraft always feels special, but even more so today: it's the first time I've been allowed to fly on a research flight!

The beginning is already known: We work through the switch-on checklist for the instrument together as usual, and I also know how to hangar the aircraft from previous campaigns. But when the door of the converted Gulfstream G550 closes, it's different: now I'm sitting inside, not watching the plane take off as usual. A quick calibration is carried out, then we taxi onto the runway and off we go towards the North Sea!

Three of the four other scientists are also flying on this test flight for the first time today. Of course, nobody wants to make a mistake here, so there is a concentrated silence over the roaring cabin interior, where we sit between buzzing instruments and eagerly follow the measurement data on the laptops in front of us.

We can communicate with the others via headsets and write to the ground via a data stream. The lectures on air pollution and measurement methods are also watching from time to time. Luckily, everything is going well while the situation starts to get exciting:

The forecast already said that a tropopause fold could be observed: A region in which sinking air from the otherwise higher stratosphere penetrates to lower altitudes. And indeed, shortly after the end of the ascent, the aircraft begins to jerk and there is slight turbulence, indicating that something is happening in the atmosphere. Almost simultaneously, the measured values begin to change: N2O decreases while ozone increases, an indication of more stratospheric air masses and thus a possible tropopause fold.

The feeling is difficult to describe, it feels almost magical: Nothing can be perceived from the outside, the air is transparent and a tropopause fold is not visible to the naked eye. But we in the plane feel how it jerks, notice how our instrument can perceive changes in the air composition of 0.0000001% and can thus make this invisible phenomenon visible. Theory becomes practice, and I will remember this day forever.

Jonas Blumenroth (IPA, JGU Mainz)

2025-12-11: EMI Test Flight of HALO

Gray clouds hang low over the airfield in Oberpfaffenhofen. A rumble is heard as the aircraft's engines start up. Then HALO emerges from behind a building, zips across the runway and takes off. After a few seconds, it disappears into the low-hanging clouds and our observation post on the roof platform falls silent.

Inside the aircraft, however, the technology is now being eagerly tested. After six weeks of installation and testing, all the scientific instruments have been installed in the aircraft and HALO is ready to take off. Today's EMI flight is the very first of the NAWDIC campaign. EMI stands for electromagnetic interference. Following a ground test two weeks earlier, the aim is to ensure that the aircraft electronics and the electronics of the scientific measuring instruments do not interfere with each other and that the aircraft still flies safely despite all the equipment. From Oberpfaffenhofen, HALO will fly to the TRA (Temporary Reserved Airspace) Allgäu and back.

Stephan is there for our team and has some time during the successful flight to take a picture of Forggensee with Füssen and Neuschwanstein Castle in front of the Allgäu Alps.

After three hours, there is another rumble of thunder in the clouds and shortly afterwards HALO taxis back onto the apron in front of the hangar. We quickly save the data and switch off our UMAQS device completely. Now everything is ready for the scientific test flight next week.

Isabel Kurth (IPA, JGU Mainz)